The first CAD system was created in the early 1960s. Modern CAD programs have never caught up.

In January, 1963, Ivan Sutherland, a PhD candidate at MIT, submitted his thesis, titled “Sketchpad: a man-machine graphical communication system,” describing his work in creating what is now recognized as one of the very first interactive CAD systems.

Sketchpad ran on MIT Lincoln Labs’ TX-2 computer. It was, at the time, one of the biggest machines in the world, with 306 kilobytes of core memory. It differed from most contemporary computers, in that it was designed to test human-computer interaction. In addition to the standard complement of I/O devices, the TX-2 had programmable buttons for entering commands, an oscilloscope/video display screen (addressable to 1024×1024 pixels), a light pen for input, and a pen plotter for output. It was, in a way, the first personal computer, albeit one that took up an entire building.

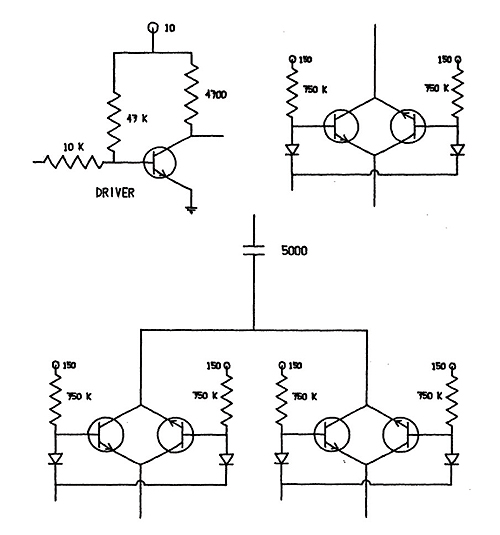

Unlike earlier computer applications, which were batch oriented, Sketchpad was interactive. Using the light pen and input buttons, you could draw directly on the screen, using a crosshair cursor. The program supported points, line segments, and arcs as basic elements, but allowed these to be saved into master drawings, which could be copied or instanced. This facility was used to create alphanumeric character glyphs, and electrical schematic symbols.

One thing that made Sketchpad really stand out was its constraint management subsystem. It not only supported explicit constraints, added to entities after they were drawn, it supported implicit constraints, created as entities were drawn. For example, if you started to draw a line, and brought the cursor close to the endpoint of another line, it would snap to that endpoint. And it would remember that the two lines were connected. If, while editing, you moved one line, the other line would move with it.

Sketchpad included 17 different types of constraints, including vertical, horizontal, perpendicular, coincident, parallel, aligned, equal size, and more. These native (or “atomic”) constraints could be combined, to create more complex relationships. Sketchpad even allowed the visual display of constraints on screen, using icons (symbols) to represent each type.

With the constraint system, it was possible to loosely sketch a shape, then add geometric and topological relationships to modify it into the exact shape you needed. It was even possible to use constraints to do structural analysis of lattice trusses, such as might be found on cantilever and arch bridges.

Visually, Sketchpad was surprisingly interactive. It supported rubberbanding when drawing or editing entities (so the entities would stretch as you moved the cursor.) It supported dynamic move, rotate, and scale of entities (meaning that they moved, rotated, and scaled as you moved the cursor.) It not only supported zoom and pan (dynamically, of course), but did so transparently—even when you were in the midst of another drawing or editing operation.

Sketchpad was designed to be extensible, with provision for adding both new graphical element types, and new constraint types. Shortly after Sutherland submitted his Sketchpad thesis, Timothy E Johnson submitted his Masters thesis describing Sketchpad III, a 3D version of the program. About the same time, Lawrence G. Roberts submitted his PhD thesis, where he had added support to Sketchpad for 3D solids, including assemblies and real-time hidden line removal.

While it’s likely that Sketchpad would have gotten plenty of attention on its own, Sutherland, Johnson, and Roberts each made 16 mm movies, demonstrating their work. A combination of these films was used in a 30-minute program in 1964 for Boston TV station WBGH. (A film that appears to be an edited version of this is on YouTube. Just search for “Ivan Sutherland.”) Further, both Sutherland and Johnson presented papers on their work at the 1963 Spring Joint Computer Conference.

Sketchpad pioneered some of the most important concepts in computing, including the graphical user interface, non-procedural programming, and object-oriented programming. If you use a computer or smart phone, you’re using technology pioneered by Sketchpad.

Sutherland didn’t rest on his laurels after Sketchpad. He went on to run ARPA (the predecessor of DARPA.) He co-created the first virtual reality and augmented reality head-mounted display. He co-founded Evans and Sutherland, where he did pioneering work in the field of real-time hardware, accelerated 3D graphics, and printer languages. He was a Fellow and Vice President at Sun Microsystems. He taught at Harvard, University of Utah, and Caltech. Now, at the age of 74, he is heading up research in asynchronous computing at Portland State University.

As a result of his work on Sketchpad, and his many subsequent contributions to computing, Sutherland has received a dazzling array of honors, including the National Academy of Engineering First Zworykin Award, the IEEE Emanuel R. Piore Award, the ACM Steven A. Coons Award, the ACM Turing Award, the IEEE John von Neumann Medal, and, most recently, the Kyoto Prize.

Alan Kay, himself a recipient of many honors for his pioneering work in computing, has described Sketchpad as “the most significant thesis ever done.” At one point, he asked Sutherland, “How could you possibly have done the first interactive graphics program, the first non-procedural programming language, and the first object-oriented software system, all in one year?” Sutherland’s response was “well, I didn’t know it was hard.”

What about CAD?

As easy as it is to trace the lines of influence from Sketchpad directly to Apple and Microsoft, it’s a little harder to trace the lines of influence from Sketchpad to today’s modern CAD systems. Mostly because those lines are so pervasive.

As easy as it is to trace the lines of influence from Sketchpad directly to Apple and Microsoft, it’s a little harder to trace the lines of influence from Sketchpad to today’s modern CAD systems. Mostly because those lines are so pervasive.

Anyone who went from MIT into the CAD industry in the 1960s or 1970s—and there were many people who did—was influenced by Sketchpad. Even Jon Hirschtick, a mid-1980s MIT graduate who went on to found SolidWorks, was influenced by Sketchpad.

Despite Sketchpad’s significance, no modern CAD systems actually trace their roots back to Sketchpad. There are a few good reasons for this: First, Sketchpad was a proof-of-concept program for human-machine interaction. Sutherland never intended it to be the basis of a commercial product. Second, Sketchpad was designed to run on the TX-2, a non-commercial research computer. It would have been difficult to port it to a commercial computer (and it’s questionable whether there were any commercial computers at the time that had sufficient capacity to run Sketchpad.)

The high costs of computing, and the lack of sufficiently good graphics display hardware made commercializing Sketchpad a practical impossibility. It wouldn’t be until 1969 that Applicon and Computervision were able to begin delivering commercial CAD systems that could actually produce drawings economically.

The deeper story

What I’ve written so far about Sketchpad could be found in Wikipedia, or in most simple histories of the CAD industry. But there is a deeper story. It starts with this observation: Sutherland never called Sketchpad a computer-aided design system. This, despite the fact that, among those supervising his work on Sketchpad were the very people who had coined the term, and defined the requirements, for Computer-Aided Design.

What I’ve written so far about Sketchpad could be found in Wikipedia, or in most simple histories of the CAD industry. But there is a deeper story. It starts with this observation: Sutherland never called Sketchpad a computer-aided design system. This, despite the fact that, among those supervising his work on Sketchpad were the very people who had coined the term, and defined the requirements, for Computer-Aided Design.

In December, 1959, The Mechanical Engineering Department and Electronic Systems Laboratory of the Electrical Engineering Department of MIT entered into a joint project, sponsored by the US Air Force, to explore the possibilities for something they called “Computer-Aided Design.”

The next year, in October, 1960, Douglas Ross, head of the Electronic Systems Laboratory’s Computer Application Group, published a technical memorandum titled “Computer-Aided Design: A Statement of Objectives,” laying out his vision. A month later, Steven Coons and Robert Mann, of the Mechanical Engineering Department’s Design and Graphics Group published a complementary memorandum, titled “Computer-Aided Design Related to the Engineering Design Process,” laying out their philosophy of approach. While each group had a somewhat different philosophy, their common goal was to evolve a man-machine system which would permit a human designer to work together on creative design problems.

At the time, MIT was uniquely qualified to take on this research project. They had the TX-0, a research computer that was optimized for exploring human-machine interaction, and, located at MIT Lincoln Laboratory was the TX-2, an even bigger research computer.

During the winter of 1960-61, Ivan Sutherland spent some time working on the TX-0, using its display and light pen. He got the idea that the application of computers to making line drawings would make an interesting PhD thesis subject. In the fall of 1961, Professor Claude Shannon signed on to supervise Sutherland’s computer drawing thesis. Among others on his thesis committee were Marvin Minsky and Steven Coons.

Though Sutherland was not a part of the MIT Computer-Aided Design Project, he was given tremendous support. Wesley Clark, then in charge of computer applications at Lincoln Laboratory, agreed to give him access to the TX-2. By November, 1961, Sutherland had the first version of Sketchpad working. This version, based on an internal project memorandum authored by Coons, could draw horizontal and vertical lines, and supported zooming of the display. In his thesis, Sutherland said “this early effort in effect provided the T-square and triangle capabilities of conventional drafting.” It was definitely more of a computer-aided drafting system than a computer-aided design system.

The version of Sketchpad described in Sutherland’s thesis was quite a bit more advanced than that first version. Based on a suggestion from Shannon, it supported both line segments and arcs. Sutherland also incorporated concepts developed by members of the Computer-Aided Design Project, including plex programming (a precursor to modern object-oriented programming), the Algorithmic Theory of Language, the Theory of Operators, and the Bootstrap Picture Language. This version of Sketchpad also included a constraint solver developed by Lawrence Roberts.

Sutherland gave a presentation on Sketchpad at the 1963 Spring Joint Computer Conference. Also speaking there were Coons, whose presentation was titled “An outline of the requirements for a computer-aided design system,” Ross and Jorge Rodriquez, who presented “Theoretical foundations for the computer-aided design system,” and Robert Stotz, who presented on “Man-machine console facilities for computer-aided design.”

Sutherland, like many other people who have accomplished great things, stood on the shoulders of giants. Clark had designed the TX-2, a computer perfectly suited to creating an interactive drawing program. Engineers at Lincoln Laboratory had optimized the design of light pens. Shannon had created information theory. Roberts had contributed solver technology. But it was Ross and Coons who provided Sutherland with many of the conceptual underpinnings that helped make Sketchpad really stand out.

Even though Sutherland wasn’t a member of the MIT CAD Project, Ross and Coons were happy to support and promote his work. They had a much larger vision for Computer-Aided Design, but Sketchpad was an excellent proof of concept, and reflected well on them.

Ross, writing in 1967, said “Sutherland’s skill, inventiveness, and diligence in expressing these powerful concepts in a smoothly functioning system, making maximum use of the powerful features TX-2 Computer, enabled Sketchpad to bring to life for many people the vast potential for computer-aided design. In particular, the widely distributed movies of Sketchpad in operation have had a profound influence on the whole field of computer graphics.”

The lessons of Sketchpad

Sutherland never wanted to create a computer-aided design system. He wanted to create a computer drawing system. That such a system could be used for drafting, or as a tool for engineering design was of secondary importance to him.

Sutherland never wanted to create a computer-aided design system. He wanted to create a computer drawing system. That such a system could be used for drafting, or as a tool for engineering design was of secondary importance to him.

Sutherland, in his paper Technology and Courage, said “Without the fun, none of us would go on!” In Sketchpad, he went as far as he could with computer drawing software while still having fun. Taking it further would have been more like work than fun (as many CAD developers have discovered over the last 50 years.) In the process of creating Sketchpad, Sutherland discovered that the most challenging impediment to making such a system practical was in the performance of its display system. In 1968, he co-founded Evans and Sutherland, and tackled that problem.

Sutherland created two versions of Sketchpad: one that did drafting, and one that did design. Even today, people who see the movies of the design version of Sketchpad are blown away by its capability. Yet, what capabilities do they look for when they go to buy 2D CAD software? Drafting.

Over time, a number of companies have developed Sketchpad-like 2D design programs featuring constrained sketching. They’ve mostly failed in the market. At the same time, AutoCAD, a simple 2D drafting program grew to become the world’s most popular CAD program. It only got constraint capabilities in 2010—some 47 years after Sketchpad had them.

The place where Sketchpad-like capability has found acceptance is in 3D feature-based modeling. The sketching modules for programs such as Pro/E and SolidWorks are very much like Sketchpad. At least, in capability. Where they fail in comparison to Sketchpad is in extensibility.

Possibly the most valuable lesson from Sketchpad may be taken from the observation that Sutherland actually built two versions of the software. When he found that the first version couldn’t be easily modified to do what was required, he started over, and built on a clean—and carefully designed—software architecture.

If you’d like to learn more about the history of CAD, including Sketchpad and the MIT CAD Project, visitwww.designworldonline.com/cadhistory.

There, you’ll find copies of the original documents that launched the CAD industry, including, for the first time since they were published in 1961, downloadable versions of the original MIT technical memos on Computer-Aided Design by Doug Ross, Steven Coons, and Robert Mann. You’ll also find a free downloadable version of David Weisberg’s 667 page authoritative history of the CAD industry, The Engineering Design Revolution.

By Evan Yares, Senior Editor & Analyst, Software (February 13, 2013)

![(Foto: JPL) [Img #9258]](https://i0.wp.com/noticiasdelaciencia.com/upload/img/periodico/img_9258.jpg)